Japanese tea ceremony’s flowing process for preparing a bowl of tea may strike one as elegant or beautiful. However, for those unfamiliar with the art, just viewing a demonstration may not provide much insight into the depth that lies just below the surface.

Tea practice evolved over time. After it was introduced to Japan from China, tea was grown at Zen monasteries. Processed and ground tea leaves were mixed into hot water to support the monk’s alertness during meditation. This emulsion supports considerable and sustained calm awareness all by itself. It was also used as a form of medicine – matcha has many health benefits.

When the warrior elite adopted the drink, they delighted in collecting and showing off costly tea utensils. These objects were used as proof of political authority, and given to generals as rewards.

In the 1500’s, merchants with Zen training adopted a style of sharing tea imbued with refined rustic simplicity. All social classes and women were invited to participate. In this space apart, all present were honored and treated with great respect. Sen no Rikyu brought this style of tea preparation to its peak. Since that time, standards for Japanese tea ceremony have been maintained by hereditary tea schools.

Business executives adopted the way of tea followed by young women who would often return to it after raising their children. Learning about the many arts (like flower arranging, brush painting and ceramics) that tea ceremony employs was another way to fill free hours. Urasenke, the largest tea school, established chapters outside Japan in 1951. They recently began publishing books in English with detailed instructions and extensive photos starting with the styles of preparing tea that beginners learn first.

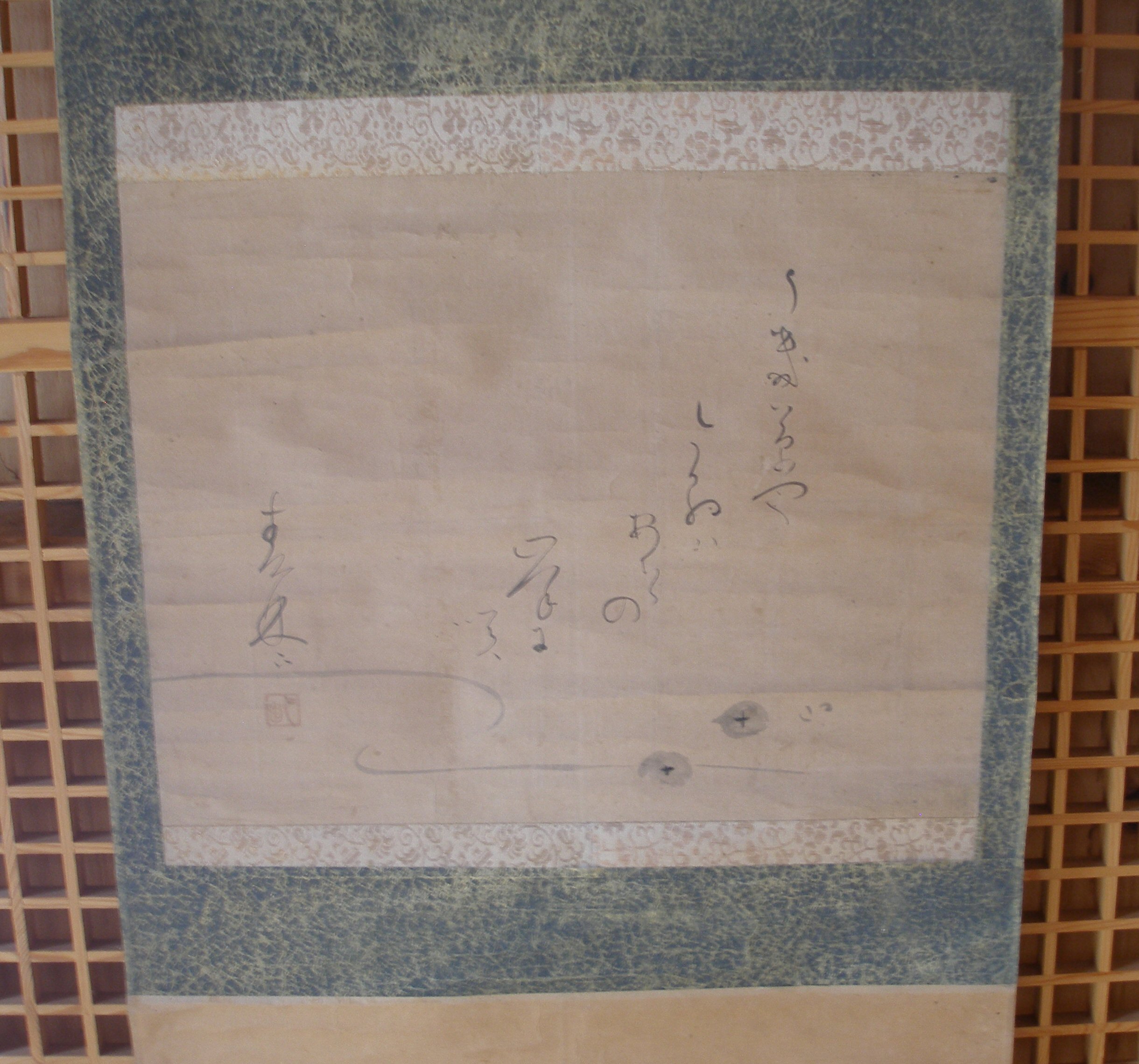

Tea practice in my tea hut (see the photo above) brings me into this season, and this time of day, embodied and grounded. There is something about the natural movements that brings one into accord with nature’s rhythms. Many comment on how time seems to slow down. With attention fully directed to what one is doing in the moment, there is no bandwidth left over for worrying about how one is perceived, or ego posturing. While you might think tea ceremony’s proscribed procedures would make it feel stiff or impersonal, it actually feels surprisingly intimate. Despite the formality, the caring generosity built into the practice is very real.

Under the right conditions, awareness may broaden to encompass everyone in the tearoom, the mossy tea garden and then expand outward from there. Even when mistakes occur or the right utensil is not available (creative improvisation is definitely appropriate per the tea literature), tea practice consistently brings me centering peace.

From tea ceremony I learned how bringing attention and intention to potentially annoying everyday activities can transform them. Washing dishes can become joyful service and meditative play. Tea ceremony teaches that it is possible to live life more like an intentional work of art with deep respect for the potential in each moment.