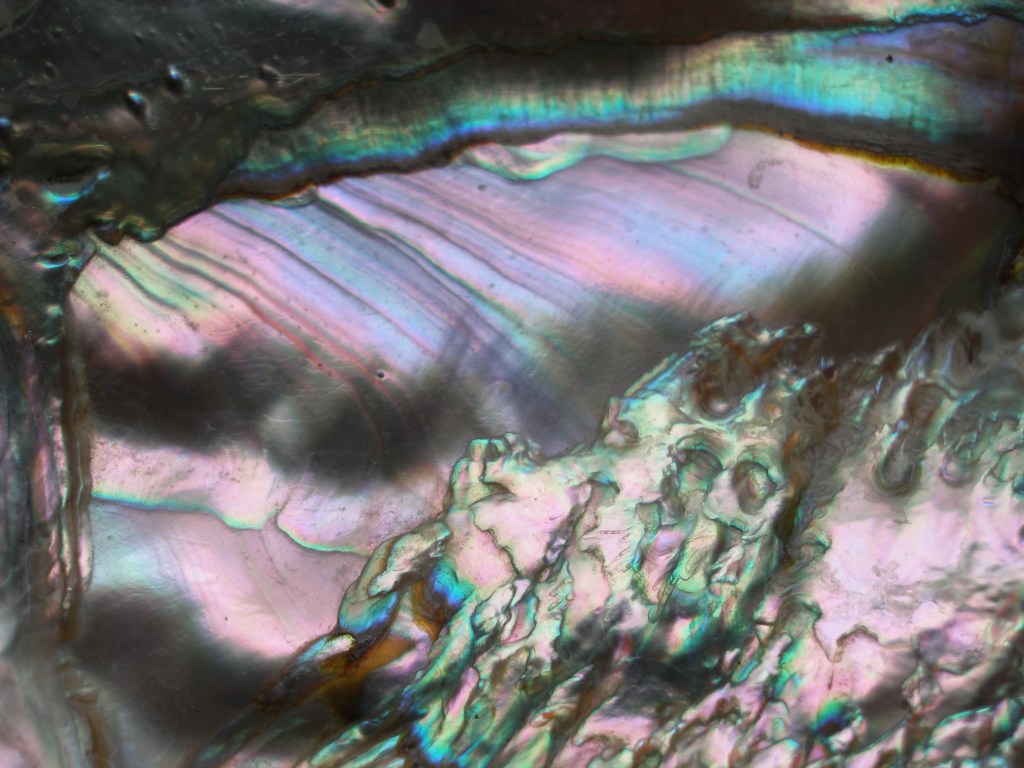

Spending more time observing nature has provided me with opportunities to observe examples of intelligent adaptation up close. When a yellow patch moved up the side of a small basin, I thought this must be a slime mold. These wonderful beings that are neither animals nor plants, make intelligent decisions. After a series of rainy days, this fuligo septica had found a suitable dry place to make a fruiting body and release spores.

Nonhuman intelligence is all over the place. I thought of the octopus in the award winning documentary, My Octopus Teacher, and parrots with brains more similar to our own. These birds make tools, dance and tap out rhythms with small sticks up in trees, seemingly for the pure joy of it. Even mice turn out to be efficient learners with aha moments. And we humans continue to learn how to make natural disasters less disastrous.

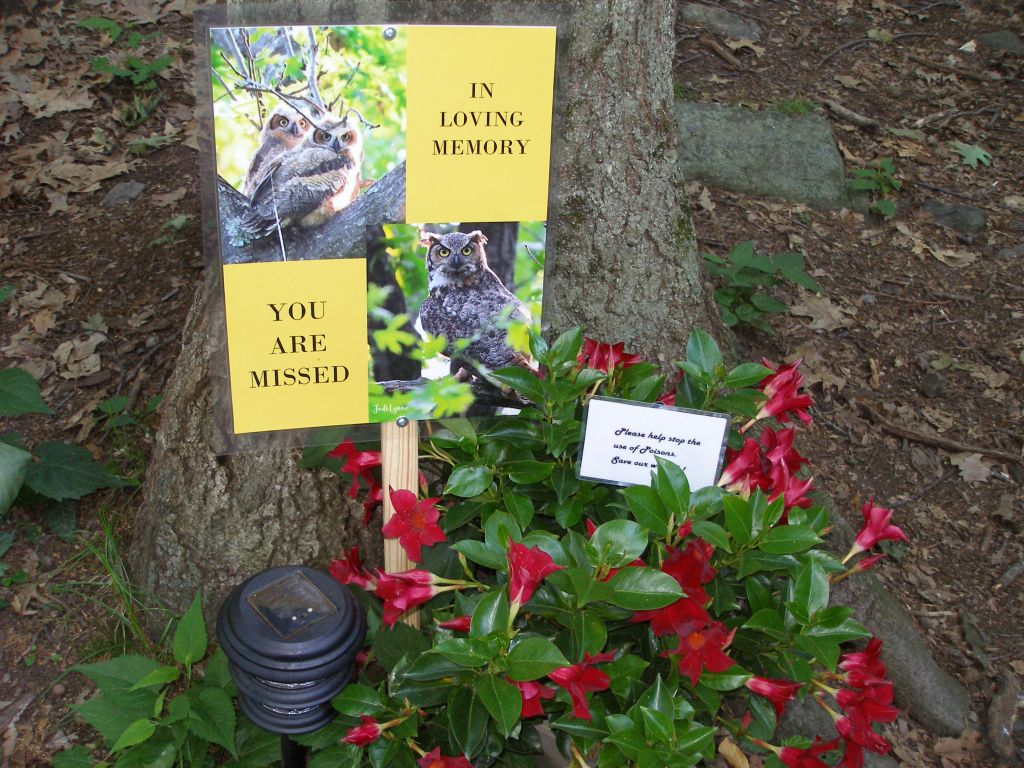

Nature is still here teaching lessons. It feels like we might be gaining a new appreciation for how much we can and should care about that. There is a new interest in trees, fungi and how we, too, are dependent upon an interconnected web of life. Even as we grieve actual and imminent losses, many are reconsidering priorities, and leaving stressful jobs with long hours. Time to appreciate and ponder may be one of the most precious resources we have.